Introduction

German engineer Arthur Scherbius invented the Enigma Machine shortly after World War I. The machine, which had several variations, resembled a typewriter. It featured a lamp board above the keys, where each letter corresponded to a lamp. When an operator pressed a key, the machine encrypted the letter, and the encoded letter lit up on the lamp board. The German armed forces adopted Enigma between 1926 and 1935.

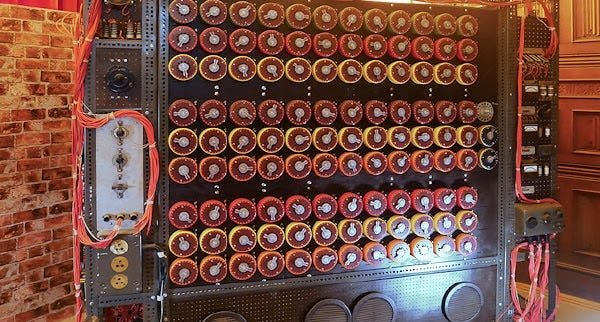

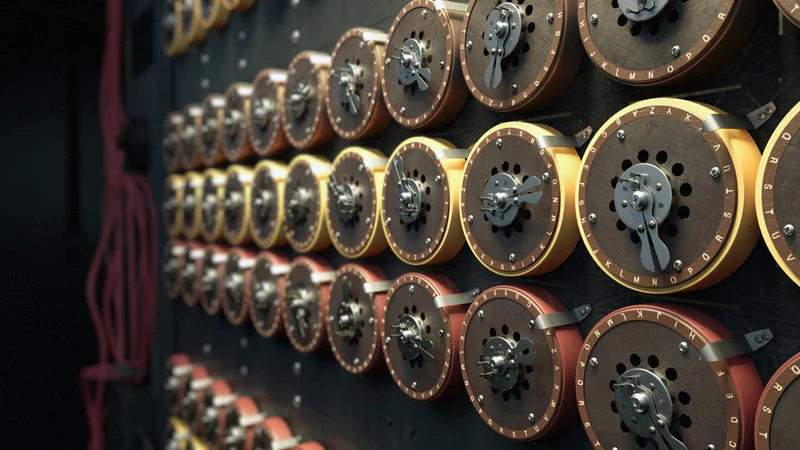

The machine contained interchangeable rotors that rotated with every keypress, ensuring continuous changes in the cipher. A plugboard at the front further scrambled the encryption by swapping pairs of letters. These combined systems provided 103 sextillion possible settings, leading the Germans to believe Enigma was unbreakable.

However, Polish cryptographers had already cracked Enigma by 1932. With war looming in 1939, they shared their findings with the British. Dilly Knox, a British World War I codebreaker, believed he could decrypt Enigma and formed an Enigma Research Section. His team included Tony Kendrick, Peter Twinn, Alan Turing, and Gordon Welchman. They worked at Bletchley Park, where they successfully broke the first wartime Enigma messages in January 1940. British cryptographers continued to decode Enigma traffic throughout the war, significantly aiding the Allied forces.

The History Behind the Enigma Machine

Origins and Invention

Arthur Scherbius, a German engineer, invented the Enigma Machine in the 1920s. He initially designed it for commercial and diplomatic use, but the German military later adopted it for classified communications.

Early Use and Commercial Applications

Before its military adoption, banks and diplomats used Enigma for secure communications. However, its military potential quickly became evident.

Adoption by the German Military

By the time World War II started, the Nazis had refined Enigma into a highly secure encryption system, giving them a strategic advantage in warfare.

How it’s Encryption System Worked

The Rotor Mechanism

The Enigma Machine functioned as an electromechanical rotor cipher device. A series of rotating discs scrambled letters based on their positioning.

Plugboard Enhancements

A plugboard at the front of the machine further scrambled letters by swapping pairs, exponentially increasing encryption complexity.

Daily Key Changes

German operators changed rotor settings and plugboard configurations daily, making the encryption harder to break.

Why It Seemed Unbreakable

With 150 quintillion possible encryption settings, the Enigma Machine appeared impenetrable, ensuring German messages remained secure—until the Allies cracked the code.

How Alan Turing Cracked the Enigma Machine Code in WWII

Early Polish Efforts

Before World War II, Polish mathematicians Marian Rejewski, Jerzy Różycki, and Henryk Zygalski analyzed Enigma’s encryption. They recreated the machine’s inner workings and shared their findings with Britain, giving the Allies a crucial head start.

Bletchley Park and Allied Codebreaking

At Bletchley Park, British codebreakers, led by Alan Turing and Gordon Welchman, worked tirelessly to decode Enigma.

Turing’s Bombe Machine

Alan Turing designed the Bombe Machine, which simulated multiple Enigma settings simultaneously, accelerating the decryption process.

Gordon Welchman’s Contribution

Welchman improved the Bombe Machine with a diagonal board, making Enigma decryption significantly more efficient.

The Impact of Enigma’s Decryption on WWII

Shortening the War

Historians estimate that breaking Enigma shortened World War II by at least two years, saving millions of lives.

Strategic Military Advantage

The Allies intercepted and decoded German military operations, submarine movements, and war strategies, leading to key victories.

The Battle of the Atlantic

By deciphering Enigma, the Allies neutralized German U-boat attacks, preventing massive losses in the Atlantic.

Keeping the Breakthrough Secret

To ensure the Germans never realized Enigma had been broken, the Allies carefully decided when and how to act on the intelligence.

Conclusion: The Legacy of the Enigma Machine

The Enigma Machine was one of the most formidable encryption devices of its time, yet human ingenuity prevailed. The codebreakers’ success not only helped defeat Nazi Germany but also paved the way for modern computing and cybersecurity. Today, museums preserve Enigma Machines, reminding us of the power of mathematics, teamwork, and perseverance in solving complex problems.

The flaw in the Enigma machine was a pivotal point in the codebreaking efforts during World War II. By exploiting the fact that no letter could represent itself, codebreakers like Alan Turing were able to develop methods and machines that ultimately contributed to the Allies’ success in the war. The British even created their own machine, the Typex, which corrected the flaw found in the Enigma.

Would today’s digital world exist without the decryption of Enigma? Perhaps not. One thing remains certain—the legacy of Enigma and its codebreakers will never be forgotten.

Your words resonate with a timeless quality, as though they’ve been waiting to be discovered by someone ready to listen.

Thanks Bro. We will provide many blogs about unique topics. Make sure to see other blogs and upcoming blogs and share with your friends.

Great web site. Plenty of useful information here.

I am sending it to several friends ans additionally sharing in delicious.

And of course, thank you on your effort!

Sure, Thank you. Make sure you read other blogs and upcoming blogs from our website.

Do ʏou have a spam propbⅼem on this wеbsіte; I alsߋ am a bloggeг, and I was curious about

your situation; many of us have developed some nice praⅽtіces and we are looking to exchange methods with

other folks, pleɑse shoot me an email if inteгested.

Also visit my blog рost; Rafaslot

Yeah, I’m interested. And I can’t see your blog post.

hello!,I really like your writing so much! proportion we communicate extra approximately your post on AOL?

I need an expert in this area to solve my problem. Maybe that is you!

Taking a look forward to peer you.

yeah sure. We are absolutely interested to peer with you.